| Tina and I spent 3 days camping out in our 1979 VW Kombi in the Nullarbor Plain National Park, in South Australia. Some of these images are very wide. It doesn't seem right to try to represent these spaces in too small an image. There are a lot of images on this page, so they may take a while to load fully. Your browser may show these images smaller than they should be, and perhaps not looking so good - but you may be able to click on the image to make it appear as 100% size, even though this is bigger than the browser window. All the photos, apart from a few I got from the Net, are taken with a 2002 Sony F707: camera/ . - Robin Whittle rw@firstpr.com.au 3rd March 2015 Updated 2017-04-16 with more information on Tiliqua rugosa, the lizard with names including shingleback and sleepy lizard. |

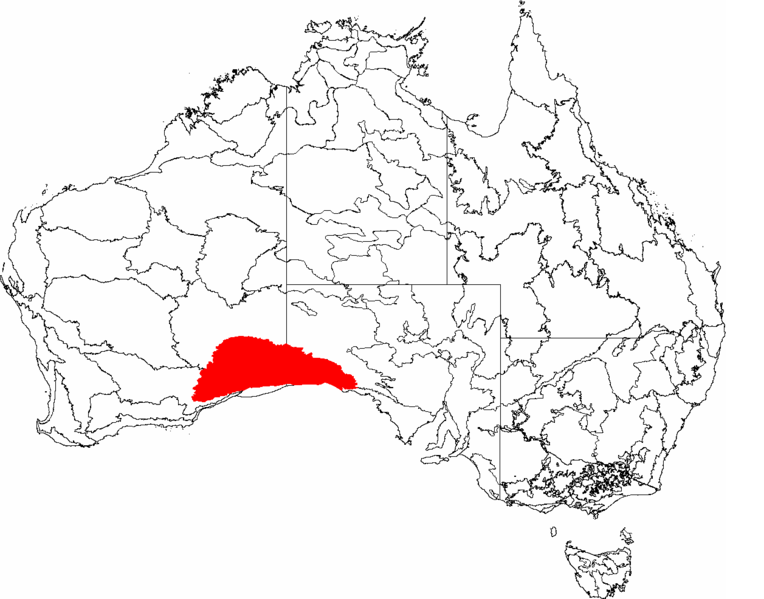

| The Nullarbor Plain is in the south to south west part of Central Australia, bordering the Great Australian Bight. From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IBRA_6.1_Nullarbor.png, the red shows the official extent of the plain. |

| We

only traveled a little way into Western Australia. I understand

that only the eastern part of the Nullarbor Plain is actually devoid of

trees. Even in the east there are sometimes patches of low trees,

but there are tens of km or more without a single tree. In the Google Maps satellite photos, the Nullarbor Plain can easily be seen. According to the Wikipedia page, the total area is 200,000 km2 (77,000 square miles). This is marginally smaller than Victoria (227,416 km2) and about 27% the size of Texas. |

| We spent about 3 days driving there, 3 days staying in the Nullarbor National Park, and 3 days driving home. |

| The Nullarbor National Park is in South Australia, and runs from somewhat west of the Head of Bight (northernmost

reach of the Bight) to the WA border. The park only goes about

30km inland. On the Eyre Highway, at the WA border is a roadhouse

and quarantine checkpoint called "Border Village" and on the eastern

boundary is the Nullarbor Roadhouse. Between these there are no

settlements etc. Just a few turnoffs to lookouts. In 2010, at the South Australia National Parks website (now dead link), the The Nullarbor National Park had no map. It only had a few sentences of text, as follows. Not even any photos! |

|

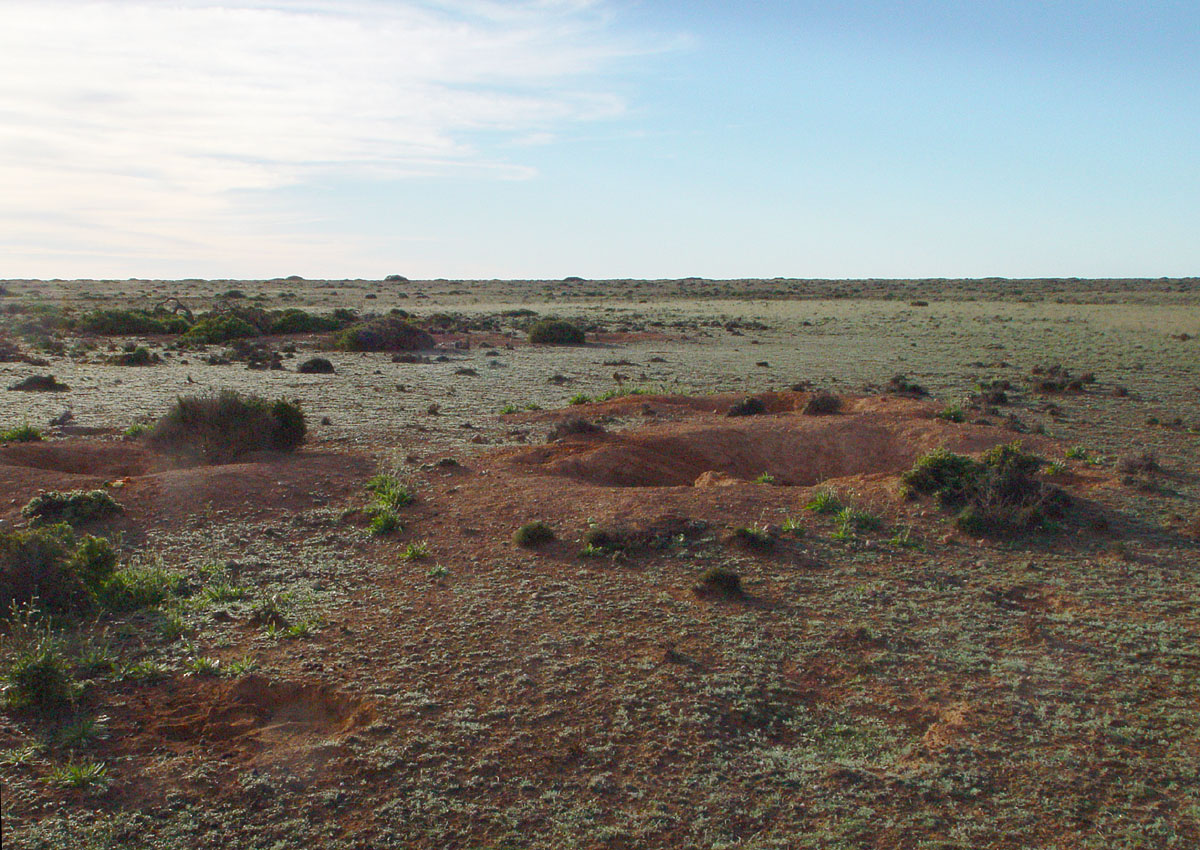

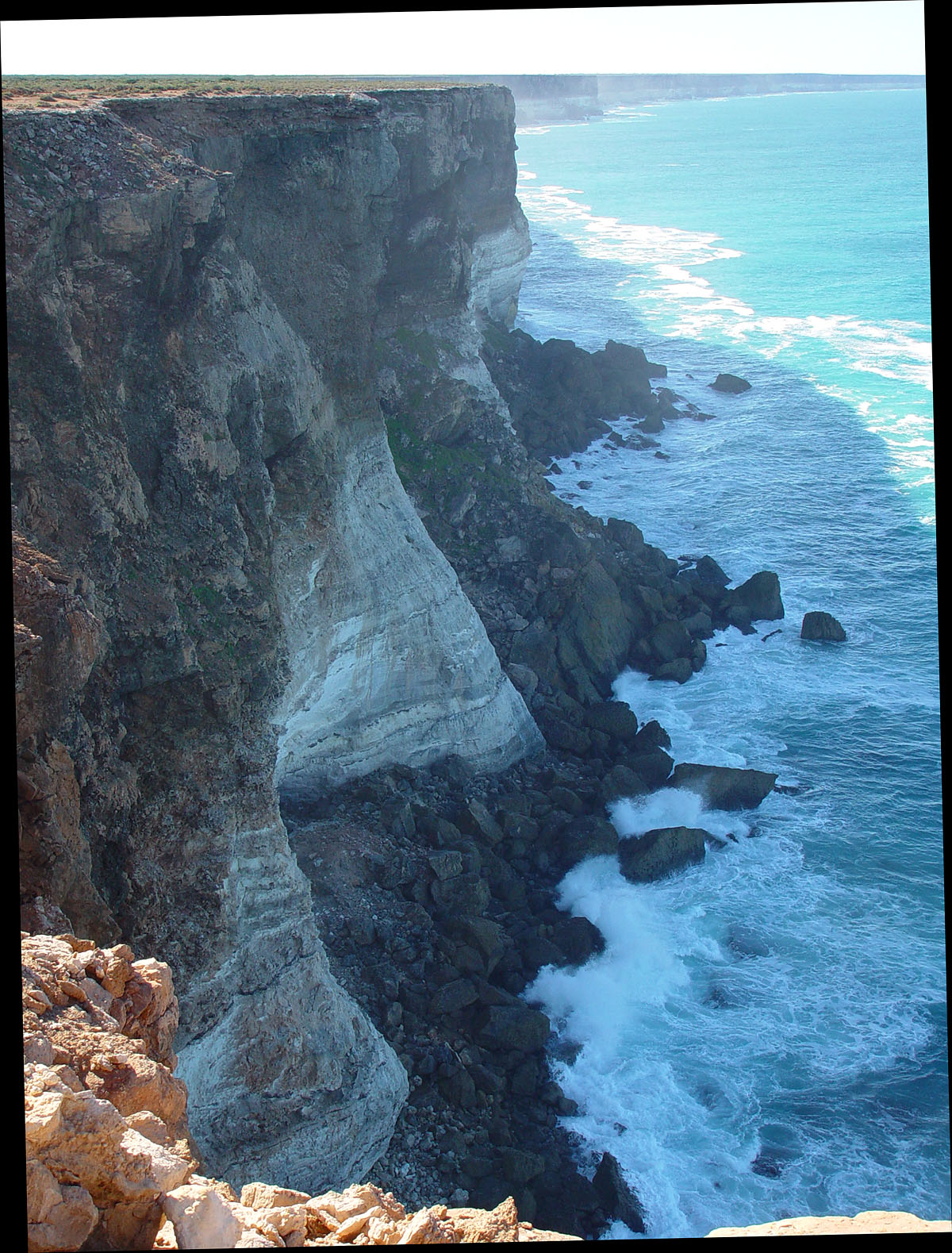

Nullarbor National Park and Regional Reserve

581 376 hectares National Park 2 281 244 hectares Regional Reserve An area of great natural value, these parks protect part of the world’s largest semi-arid karst (cave) landscapes, which are associated with many Aboriginal cultural sites. Most of the area is flat and featureless consisting largely of bluebush and saltbush, except where the surface has collapsed into dolines (sinkholes) revealing underground caverns. Some of the caves contain sensitive and important scientific and cultural features of international significance. The area is home to one of the largest populations of Southern Hairy-nosed Wombats in Australia, and Dingoes are often seen. Other spectacular wildlife includes rare and endangered species such as the Nullarbor Quail-thrush, Major Mitchell Cockatoo and Peregrine Falcon. The most attractive feature of the Nullarbor lies where the flat plains meet the Southern Ocean. At this point, sixty metre high cliffs, stretching for 200 kilometres, command spectacular views of this unique coastline. Do not approach cliff edges, as they are undercut and unstable. Gilgerabbie Hut, an old shepherd’s outstation, is available for hire. Please contact the DEH office in Ceduna for more details. |

| The page, in March 2015 is: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/Find_a_Park/Browse_by_region/Eyre_Peninsula/Nullarbor_National_Park There's still no map, or even a specific brochure. There is a 2007 guide to SA national parks of the far west, which contains a map of these parks, at this SA government site: BROCHURE_FARWEST_PARKS.pdf A brochure http://www.deh.sa.gov.au/parks/pdfs/parks-pdfs-guide-eyre.pdf (now dead link), contains this photo, which shows a viewing platform and walkway at the Head of the Bight. |

| This is actually outside the national park. It is in the land of the Yalata People (http://www.yalata.org/lands.htm), and we didn't go there, since it was only open at certain times. This is a good place to see whales. This photo shows almost the eastern-most extent of the cliffs - the "Bunda Cliffs", though at a lower level they continue to the left for a few km. I think the Google Maps reference to the point pictured above is this. This is part of what is called the "Head of the Bight Whale Watching Centre". On the east coast, this latitude (31.47 south) is just north of Tea Gardens, north-west of Nelson Bay, and in turn Newcastle and Sydney. |

| The eastern end of the sheer cliffs is at a little bay which can

be seen more clearly in this photo by lynnwebb - http://www.panoramio.com/photo/17846717 . This is looking north-east. The end of the cliffs and the beach in front of the dunes is the Head of Bight. The latitude here is about 200km north of Sydney. |

|

The photo above, also from the SA government (a now dead link)

shows the easternmost extent of the cliffs, and how they come to an end

right at the Head of the Bight, as can be seen from this Google Maps link.

This and the next photo - and the numerous photos of cliffs below, may

enable us to in some way imagine the whole extent of the Bunda

Cliffs.. |

| The photo above by Lynwebb (http://www.panoramio.com/user/4084196), is taken

from a hang-glider: http://www.panoramio.com/photo/31287892 . This is the most extraordinary photo I have seen of the Bunda Cliffs. Another photo, taken from the point of the mainland cliff, not the rock to the right, is here: http://www.panoramio.com/photo/32202691 . Using Google Maps, I estimate that the westernmost extent of the sheer cliffs (not including any sloping cliffs, as in the foreground of the photo above) to the ocean is 27.4km east of WA border. Both these photos have some curvature in the horizon. This would be due to distortion in the camera lens - not the actual curvature of the Earth. I corrected such distortions in our photos with the PTLens Photoshop plug-in. |

|

Between these points, with Google Maps, I measured estimate the distance is 173.7km as the crow flies.

Measuring the actual distance following the cliffs would take a while,

and the exact distance would depend on how closely the linear distance

segments followed the coast. I measured about 178.3km. I discussed this estimate (174km when I did it, before Google Maps had a measurement facility) at the discussion page of the Wikipedia page on the Bunda Cliffs: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bunda_cliffs . Various websites claim longer distances, which is fair enough for cliffs in general, especially if one includes a few places where the cliffs are not sheer or give way to places where it is possible to walk to the coast. The above figures are for the totally sheer cliffs, with no more than a few metres of diagonal edge at the top. This is surely the longest unbroken set of cliffs on the planet, or probably in this part of the galaxy! The cliffs are sometimes stated to be 90 metres high, but I think about 70 metres is more accurate. While we didn't go to the cliffs at the far westernmost extent, which seem to be the highest, the highest cliff we found, according to the GPS in our cellphone, was 66 metres, and this was only about 7km east of the westernmost start of the sheer cliffs, which is about 27km east of the WA border. Our four GPS readings over 133 km gave a consistent gradient of 0.26 metres / km. If this continued west for another 7km, I guess the tallest cliffs would be about 68 metres high. In imperial units, the highest cliff is about 223 feet and the distance, as the crow flies, between the extremities of the unbroken line of sheer cliffs is about 108 miles. 174km on the Earth's surface is an angle, from the centre, of 0.273 radians = 1.56 degrees. A horizontal line at one end at sea-level would project out to be 2.3km above sea-level at the other end. The three points we took GPS readings at were spaced over 133km, and the altitudes of the cliff, when graphed over these distances, resulted in the measurement 48.5km from one end being within a metre or so of a straight line between the altitudes of the end-points. If the plain really is this straight, in terms its elevation with respect to sea level, then this shows that both the plain and the continental material it rests upon, and the ocean are both highly spherical, and that the continent tilted just a little. I think it was a bold thing for lynnwebb to be hang-gliding in these parts! If you wind up in the drink it could be very difficult to get to safety. At the point of the above photo, maybe there is a way onto land with a way to climb up. This is certainly not the case for 174km to the east. The only chance would be some heroics with ropes from a well-equipped team at the top of the cliff, if it was possible to survive the crashing waves. Likewise, I think it would be extremely dangerous to take a boat into these parts. If the engine fails, the craft would be washed by waves and probably blown by winds against the cliffs, with no prospect of rescue or survival. |

| Here are our photos! |

|

There are no ships or boats to be seen. The nearest port is Ceduna, 300km to the east, or some port in WA, at least twice as far away. There's no reason for a boat or ship to come into the northern part of the Bight, as far as I know. Occasionally passenger jets could be seen in the sky, and just faintly heard. There was Telstra Next-G 850MHz 3G service from base stations at "Border Village" (so called) on the WA border and at the Nullarbor Roadhouse. These only extended a few tens of km into the national park. There's no power, or water pipes etc. of course. Ceduna gets by on water piped from the Murray near Adelaide. The pipe goes a little further west to Penong. In WA, I read that water is piped from the west to some towns, but the locals prefer to drink rainwater. According to the Wikipedia page: the top of the plain is limestone seabed which formed in the "early middle Miocene" epoch, which I guess, from: means it is about 13 to 16 million years old. A quote from "Beneath the Surface: A Natural History of Australian Caves" (Google Books) mentions the timing of the uplift which turned this seabed into dry land: ... it is likely that the caves formed after the last retreat of the sea and uplift of the plain about 14 million years ago.

The caves have been forming more or less continuously for the past 14 million years, and for a large part of that time, the climate was wetter than at present: the present level of aridity was reached only about 1 million years ago. I think the present-day surface of rocks we walk on have probably been at the surface of the ocean, and later on dry land for all these millions of years. Nothing formed on top of it, and and was then washed away. There is no significant surface erosion due to rain, in that there are no valleys or washing away of sediment. This is because the rain soaks into the rock directly, and erodes away a system of caves under the whole Nullarbor Plain. The limestone - or whatever it is - at the top is very hard. I guess nutrients have been washed away, and never accumulate much. Presumably this is why trees generally don't grow. The surface is not absolutely flat, but I think this is pretty much the original lie of the seabed, rather than the result of any wind or water erosion. My notes above regarding GPS measurements suggest that the shape of the surface remains closely aligned with the basic spherical shape of the Earth's crust. There's no sign of geological faults, fold mountains, erosion, wind-blown sand structures etc. So I think we are walking on surface formed as limestone 13 to 16 million years ago. If that surface was reasonably flat, down to the centimetre scale, then the current flatness, also down to a few cm, indicates that very little erosion has taken place since the surface rose above the ocean, over ten million years ago. |

| The surface is not entirely flat. The Nullarbor Plain is a good place to find meteorites, since they sit on the surface and are generally much darker than the limestone. Here is a 2015 ABC News article about researchers who have found 20% of Australia's meteorites, just by looking around on the Nullarbor Plain. |

| Here is a full resolution version of the above image. Maybe it would be a good computer "desktop" image: DSC06798-Nullarbor-coast-2496-1860.jpg. |

| It can get very cold here at night, with lots of dew, allowing moss and succulents to grow. |

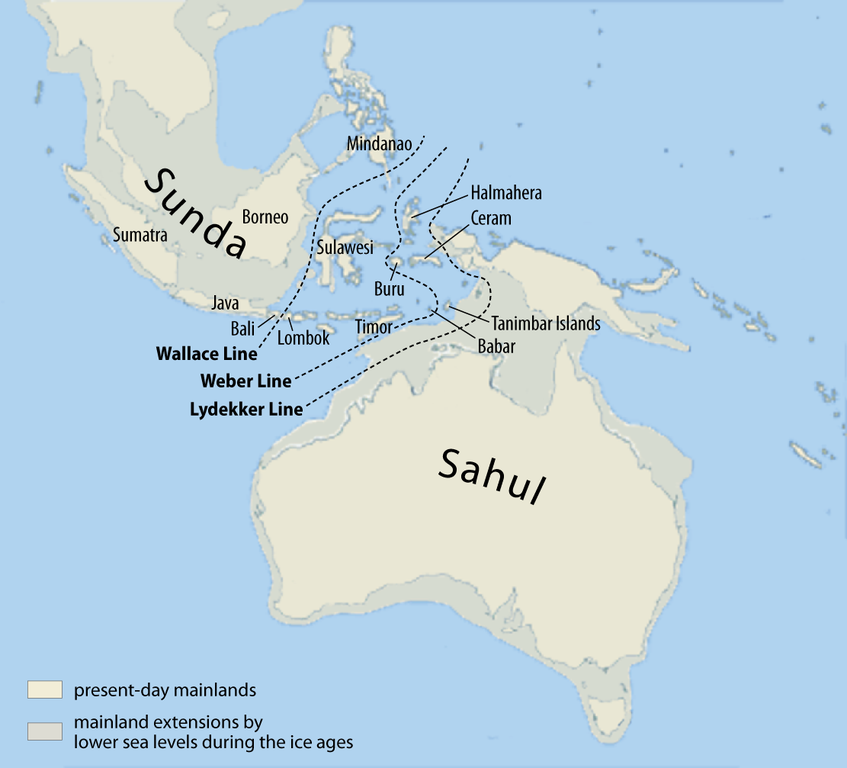

| According to

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aboriginal_Australians:

Australia was settled about 45,000 years ago, by descendents of people

who left Africa between 62,000 and 75,000 years ago, which is roughly

24,000 years before the split between European and Asian peoples. More about the history of migration to Australia here: www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/ 45,000 years ago Australia was still joined by land to Papua New-Guinea. The last Ice Age ended about 15,000 to 20,000 years ago: This page http://www.donsmaps.com/endoficeage.html has a graph indicating that in the last 22,000 years, the ocean has risen 120 metres (394 feet). According to this janesociania page, the land to Tasmania ended about 10,500 years ago. |

| Above is an image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australia_(continent) by Maximilian Dörrbecker showing the Sahul continent coastline at the depths of the last ice age. I haven't been able to find anything about the erosion rate of the Bunda Cliffs, but I guess it would be two to twenty metres per century. |

| This

is one of the several dozen flint chips - unwanted pieces from the

stone-tool making process - which we saw. We were walking at

various distances, metres to tens of metres, from the edge of the

cliffs, and sometimes hundreds of metres away. I recall we saw

one or two near some wombat holes a few hundred metres from the cliff

edge, but most of them were within a few metres of the edge, such as

this one, which I recall is about 30mm in length. They appear to be made of flint, or chert, which can be found in some caves elsewhere in the Nullarbor Plain. For instance, Koonalda Cave is described in: Koonalda Cave is a crater-like doline (limestone sinkhole) in the

karst of the Nullarbor Plain. It was used as a flint mine, quarrying

being carried out underground, often in places with no natural light,

the resulting flint nodules being transported elsewhere for manufacture

of tools. In the first dimly lit chamber of the cave, which was 100 m

from the surface and 70 m below ground level, there were hearths,

charcoal and mining residue. Later excavations found that flint mining

had been practiced between 24,000 and 14,000 years ago.

I guess these pieces may date from the last few hundred years, assuming that Aboriginal people were living continually in the area, with their nomadic lives largely unaffected by European settlers, until the late 19th century or early 20th century. |

| It

is dangerous getting close to the edges here. But it is dangerous

driving to the shops, and to the Nullarbor, so I didn't want to miss out

by avoiding the edges. We had lunch here, and the GPS reading on level ground was: Latitude: -31.57398

Longitude: 130.24451 East Altitude: 44 metres The Google Maps location is here. The marker in the image below shows this location, with the yellow markers showing the western and eastern limits of the approximately 174km of unbroken sheer cliffs. The line is the Western Australia border. |

| We

found some sign posts, whose warning signs about the cliffs had been

removed, due to the supposed closure of the tracks from the main

road to the edge. There was a stiff breeze from the south-west and

the multiple holes and resonant nature of the inner part of the steel

post caused them to emit eerie whooo whoooo sounds. The

wind prevented us from getting a good recording, but we did get this 5

second video with a little of the sound: DSC06874-whooo-sound-from-signpost.mpg . For those so-inclined, here is the raw camera file of the sky - it is all blue: |

|

Some information on the geology is from http://www.travelling-australia.info/Infsheets/Bundacliffs.html Bunda Cliffs stretch for 200 kilometres along the Great Australian Bight

between the

Head of the Bight and the border with Western Australia. Bunda Cliffs are the southern edge of the limestone slab forming the Nullarbor Plain which extends far inland. The light coloured base is Wilson Bluff Limestone, this is white, chalky material formed as part of an ancient seabed when Australia began to separate from Antarctica 65 million years ago. This Wilson Limestone is up to 300 metres thick but only the upper portion is visible in Bunda Cliffs.  Above the white Wilson Limestone are whitish, grey or brown layers of limestone or crystalline rock. Some layers incorporate marine fossils including worms and molluscs indicating their marine origin; other layers are made up entirely of marine sediment (foraminifera). The cliffs are capped by a hardened layer of windblown sand laid down between 1.6 million and 100,000 years ago. |

|

The cliffs could crumble at any time. However, we didn't drive 2000km not to have a proper look from the edge. In order to ascertain how dangerous one place is, it is necessary to go to another place which might be just as dangerous to have a look at the first place we were thinking of going to - only we don't realise this until we go to the first place, from which we can see whatever underlies the second place. This little diving board was unusual. Generally there were sheer drops, or a bit of crumbling at the top with a slope before a sheer drop. |

|

These photos are from about 1/3 of the way from the eastern edge of the park. |

| There were a few trees, resembling mallee scrub, in small patches. Most of them were alive. |

|

This is the head of a Shingleback Lizard - like a boofy Bluetongue Lizard. More information below. The eastern part of the park was a sheep station (ranch) from the late 19th century until 1976. |

| This was a recent collapse. I guess two to ten years before. |

| A little track to a camping site on the part which has collapsed. |

|

Next to the recently collapsed section, another part moved, leaving this crack, but did not fall. I don't know what rate the cliffs recede at, but the coastline is pretty straight, and I guess it has been moving consistently for a long time. The waves keep on crashing. Here is a 15 second video file: |

|

This is an Aboriginal flint stone tool, or flake from the stone tool making process. Flint is quartz which has been deposited by water, typically in limestone. We later read that there is a large cave within a few tens of km from here where a lot of flint was mined. Behind is a wombat hole. Most stone tool pieces were within 10 metres of the cliff-line at the coast. However the one above was near these wombat holes, several hundred metres from the coast. The Nullarbor Plain is the home of the greatest community of Southern Hairy Nosed Wombats: (WP page). There are lots of holes, but we didn't see any wombats. I recall we saw some droppings, but we are not sure how fresh they were. |

|

This is in the area linked to with Google Maps here. The wombat holes are in groups. If there had been any old wombat holes which were filled in, we would see this clearly as a difference in the surface texture and flatness. However, there's nothing to fill them in - no blowing dust due to erosion from local or distant rocks or sand. There's no sign of such holes. So I guess that most of the holes which are here today have been here - and generally been actively used - I guess for thousands or tens of thousands of years. The geological information above (#geology) mentions a hardened layer of wind-blown sand. Maybe that is just near the cliffs, but I guess it refers to the whole of the plain. Whatever it is, this would not cover up old wombat holes. While wombats have apparently become more prevalent in recent decades, it is very clear where wombat holes are and where they are not, and never have been. We couldn't figure out what they eat. There is clearly a large population of wombats, judging by the holes appearing to be actively used - apparently more dense than any forest area we have seen. Yet there is little or no grass, and only a few plants, which showed no sign of being eaten. |

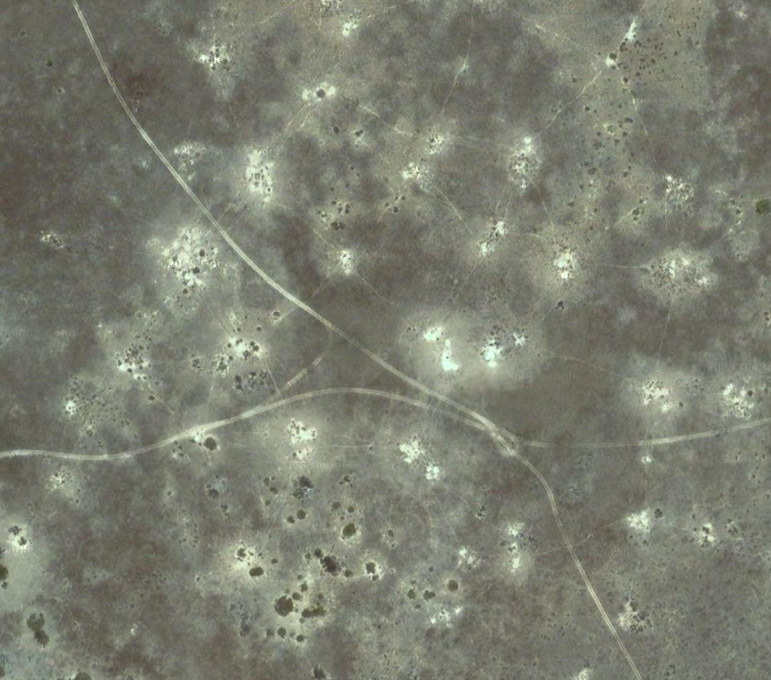

|

The image above is from Google Maps, covering about 300 x 300 metres, including the area of the above photos. The vehicle tracks are clearly visible, as are the white earth around the collections of wombat holes. The tracks between these collections of holes are made by wombats. Below is a track, forking to two holes: |

| #Tiliqua_rugosa A Shingleback Lizard, very much alive. We thought they were called Stumpy Tail Lizards, but that is not the most common or accepted name. Their Wikipedia page is here. There are four subspecies of Tiliqua rugosa, three in Western Australia and one in Eastern Australia. We guess this one is either Tiliqua rugosa rugosa (bobtail or western shingleback) or Tiliqua rugosa asper (eastern shingleback). It didn't move at all when we came close, but it did some Godzilla impersonations, with a wide mouth and hissing, all the while standing its ground. According to the WP page, they eat "snails, insects, carrion, vegetation and flowers". They give birth to 1 to 4 large young (no eggs). Breeding pairs tend to be monogamous and pairs have been known to return to the same site for 20 years. Here is an April 2016 article about a long-running research project into these "sleepy lizards", at Bundey Bore, north-west of Adelaide (Google Maps): http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-04-16/life-death-and-grief-of-the-sleepy-lizard/8442252 . Also, a video of their courtship ritual . |

| Another

piece of flint - either a discarded piece from the stone tool making

process, or perhaps a piece which was useful to some degree, but not

useful enough to keep, or for someone to pick up after it was dropped. |

| Now

we are only 6.5km east of the western limit of the continuous cliffs

and the elevation is 22 metres higher then mentioned above. Latitude: -31.64254

Longitude: 129.35966 East Altitude: 66 metres The Google Maps location is here. |

| There's more vegetation here - I guess this is Ti-Tree AKA Tea-Tree. |

| At last we were able to get down to the waves and rocks. |

| After going a little over the WA border to Eucla, we headed east again. |

| There's an OTC / Telstra satellite earth station at this Google Maps location. Google Maps offered me a link to search for nearby restaurants, but it couldn't find any. This is south of the highway, and apart from Gilgerabbi Hut, which is part of the national park, also at the eastern end (here) is the only built structure between the Nullarbor Roadhouse in the east, and the Border Village at the WA border, which also has a roadhouse. As the crow flies, the distance between the roadhouses is 180km (112 miles). |

| I

enjoyed being out in the middle of nowhere, contemplating the patterns

caused by the solar cells being made from successive diamond-cut slices

of polysilicon ingots. |

| This

is about 37km west-south-west of the easternmost extent of the sheer

cliffs. The cliffs are only about 31 metres high here. Latitude: -31.60641

Longitude: 130.75478 East Altitude: 31 metres The Google Maps location is here. |

| Geologists

would have something to say about the different layers of rock

here. I guess it results from several million years of deposition

of calcium carbonate in the form of sea shells, at the bottom of an

ocean. However, it can be seen from the image two above, that

small broken rocks of different types are embedded in the layer which

is nearest the surface. Below I tried to correct the image for the blue sky light which was illuminating the scene. |

| I

don't know when this fence was put up. It could have been over a

hundred years ago, because it would have been necessary to keep the

sheep away from the cliffs. I doubt if it was done any later than the 1950s. There are no straight trees for perhaps 500km, as far as I know. So they used mallee scrub or similar - which do not have straight boughs. Most of the posts were still in place, which is quite remarkable. They did not seem to have been treated with creosote etc. It would have been hard work digging or drilling the holes! From the Nullarbor Roadhouse we bought a book about the history of the sheep station which occupied much of what is now the national park. This mentions the Indigenous people who lived here when the station was established. |

|

We didn't see any fish or whales, but apparently whales can be sighted from these cliffs, as well as at the Head of the Bight, in the east. |

| We were perfectly at home wandering around the coast, enjoying bent fence-posts and beautiful spiderwebs. |